![]() THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD

THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD

by Alphonse Dion

She was born to Alex and Isabel Gadwa on a bright September morning in 1902. All that day and the following night, Isabel Gadwa had lain on her straw-stuffed canvas mat with her teeth and fists clenched as the pain racked her body. No Indian woman had ever been known to voice her sufferings and she wasn't about to break the tradition even though this was her first baby. When the morning dawned, she had given birth to a little girl. Later, the mid-wife placed the tiny bundle of humanity in her arms and she whispered softly to her baby.

When the time came, they christened her "Mary Louise." The years passed and the toddler soon learned to walk and then to run. Some evenings she would sit at her mother's feet after she had lit the wick lamp and listened to the stories about her ancestors who had come west in a crude red river cart in search of a better life. They hadn't found it but they had stayed, determined to eke a living out of the barren ground of the Kehewin reservation. She never tired of listening to how they had pushed relentlessly westward until they had stopped to rest on top of the hill overlooking the Kehewin valley and lake. The beauty of the land captivated them and they moved on west no more.

He was three years old at the time. His parents, Augustine and Marie Dion called him Toussaint because his birthday fell on the eighth of November, All Soul's Day in the Catholic religion. Augustine and Marie had moved in from Onion Lake, and like the Gadwas had chosen Kehewin for their home. Augustine was a man of means and over the years had managed to build up his cattle and stock population to quite a respectable number. He insisted on education for his children. His eldest son became a school teacher. None of the others could tolerate the incarcerating atmosphere of a boarding school. Toussaint stayed a day in the Onion Lake Boarding School and left on foot early the next morning, to begin life without books in the hills of Kehewin.

A few years later, Alex and Isabel Gadwa bade a sad farewell to their eldest daughter Mary Louise who would be attending the Onion Lake Boarding School. She was to stay there for two years during which time she worked her fingers to the bone scrubbing hardwood floors and mending endless piles of worn-out clothes. She came home a hardy girl and the few words she had learned to speak in the English language soon faded as the summer breezes of the Kehewin valley touched her face.

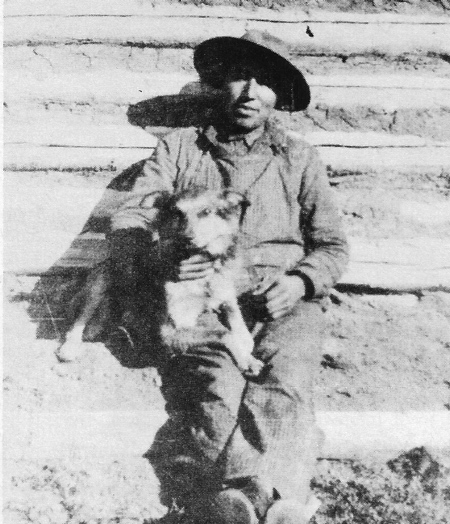

Toussaint in 1917

Marie Louise on their wedding day in 1918

She was fifteen, then, and her parents were beginning to pick out worthy suitors. Toussaint, son of Augustine and Marie Dion, would be a fine match for their daughter, they decided. A meeting between the two sets of parents would determine the futures of Toussaint and Mary Louise.

On February 21, 1918, Toussaint and Mary Louise found themselves standing before the priest in the St. Louis Parish in Bonnyville, Alberta. The strange words the pater uttered whirled in their minds. The words they barely understood would hold them together for the next fifty-one years.

The church bell began to chime as they stepped out of the church and into the waiting horse-drawn cutter. For the first time they held hands and the grey sky began to shed huge billowy snowflakes. Out of town and across the lake the cutter sped and soon the snowflakes became a blinding mass of winter fury, but still the church bell chimed on.... fainter and fainter until the howling wind drowned all else.

The first years of their lives together were dominated by the need for survival. Each new day brought them together as they struggled to make it on their own. The plague of that year claimed the lives of many of their friends. The stronger men of the reserve who were not taken with the sickness dug graves for their dead friends. The death toll mounted until Toussaint and other men had to dig huge graves and hold mass burials for their departed. This was the flu that followed the white man's World War of 1914 - 1918 and the epidemic was world wide. Although at that time the Indians were not aware of this.

When the first warm breezes heralded in the spring, sorrow hung heavy like an ocean mist and soon the April showers would drench the graves and coax the flower buds into blossoms. The rain mingled with the tears on the faces of the people whose friends and relatives had died. Some entire house-holds were cleaned out. In one household, Toussaint and the other men found both parents and two children dead. Only the youngest a toddler, was alive and trying to nurse on her dead mother's breasts. They bundled up the baby and dropped the bodies of the family into the pine box coffins.

Slowly the people began picking up the pieces of their shattered lives as the seasons passed. It wasn't until June of the next year that Toussaint and Mary Louise welcomed an addition to their family. As her own mother had done, Mary Louise cradled her baby in her arms while the June lilies outside her window nodded lazily in the afternoon sun. After some debate, they decided on a simple, sweet sounding name; Delma.

Two years later, Alice was born to them. With two little girls in the family, Toussaint and Mary Louise worked from dawn till they could no longer see anything in the evening. Toussaint hitched himself to the plow with one cow and two horses as the one-bladed plough dug a single furrow in the ground. His wife held the reins and the plough with baby Alice strapped to her back. Occasionally dinner would consist only of stewed gophers. At nights they would stumble into bed too weary to speak and slept the sleep of the exhausted only to begin the ritual with the break of morn.

Only their belief in the Almighty sustained them through those meager years. They had become gaunt and sparse as they drove their bodies up to and beyond the point of physical endurance. Sometimes, Mary Louise would stumble and fall behind the plow as tears blinded her eyes. On one such occasion when she could continue no longer, she stumbled and there in the furrow was a beautiful black, wooden rosary neatly laid out in a circle. She gathered the rosary in her palm and gazed at the wounds of Jesus on the cross. She picked up her burden and smiled as she urged her team onward with the plow.

In the sixth year of their marriage, Helen was born to them. She was a sweet child with laughing eyes, who loved her parents with all the simple innocence of childhood. Life had never held any sweet promises for their small family but the joy the three girls brought to their parents erased all memories of the days hardships and helped to strengthen their faith with the love they had for one another.

The seasons changed and the months became years. Through their untiring efforts, they had managed to put a few acres under cultivation. Life had improved some..that is, until they noticed their eldest child Delma losing interest in the games the little girls played. She would go into coughing spasms as her little body shook with the disease that lay within. In the fall of her eleventh year, little Delma quietly slipped away into the land of cherubs. As the leaves fell from the trees in a blaze of glory, her life ebbed from her until she drew her last breath and passed on.

It was as if a part of them was buried with their little girl and they could not reconcile themselves to their loss. They poured out their love to the two remaining little girls and in their childrens' eyes, they saw their love returned a hundredfold. Two years had passed but each new day seemed to bring a fresh memory of their little Delma.

It was winter again and Toussaint planned to go north of Kehewin by dogteam with Albert Johnson for the winter's catch of furs. Early one morning he hitched up his dogteam and after kissing his little girls good-bye left for for his trapline. Once he turned and saw his little girls, Alice and Helen, waving at him. It was the last time he would see Helen alive for she died of ruptured appendicitis the next day. That spring, they would take long walks with Alice walking between them. She would ask about her sisters and soon they would all be crying as the sun cast a last scarlet ray over the horizon.

Nothing could erase the constant stabs of pain they felt in their hearts over their loss. Mary Louise would often console herself of her daughter's last moments. The peace she saw on her little girl's face would shine like a mirror forever in her memory. She had tried so hard to save her; she had hitched Tom and King to the sleigh and covered the distance to the hospital in two hours.. That night, the kindly Dr. Miller had allowed her to remain in the sunporch of the hospital with her baby's body. She sat all night in silent grief and fingered the rosary she had found in the furrow so many years ago.

Spring gave way to summer and with the summer came the rodeos. There was news of a big up-coming rodeo in Hobbema and Toussaint was keen on going. He loved rodeos and often competed. Out in the timber corral behind his father's house, he had ridden many a cayuse to a trembling standstill. A big rodeo meant bigger prizes so he packed up his small family and started the one week journey by team to Hobbema.

He drew a stark black chute-fighting bronc. The chute opened and the high-kicking bronc spun like a top as it sought to unload its burden. The bronc straightened for a minute and reared at a crazy angle and came crashing down on Toussaint. Every fibre in Toussaint's body screamed with pain until the blessed darkness filled his mind. They carried him out of the corral and loaded him into his wagon. The jolting of the wagon dizzied him with pain; his wife had begun the long trek back to Kehewin with a battered cowboy in the back of the wagon. One whole year was to pass before Toussaint could attempt his first faltering step and even then the sweat that glistened on his forehead told of the ride he'd had on a devilish bronc.

In his delirium, he'd seen familiar faces come and go. Sometimes he would hear snatches of conversation; something about crops, winter, babies, no baby...His brothers, neighbours and relatives had come and put in his crop for the winter. His wife had given birth to a boy in the meantime. She called him Willie James. Their hearts swelled with pride and the happiness Toussaint felt encouraged him to get well.

Slowly, Toussaint regained his health and everything seemed to be improving again. The stock had survived the winter and the spring saw the birth of more calves and colts. Maybe now the happiness they'd both hoped for would come to pass. Alice was now almost thirteen years old and she could do most of the household chores and care for the baby while her parents toiled outside.

The snows of winter came and buried the barren sullenness of autumn. Just a short while since, the trees were clothed in a majestic splendour of glory; now they stood in naked rows bowing to the fierce north wind. In a few weeks time, it would be Christmas. Someone would put up a party and they would dance while the fiddle whined far into the night. The homebrew would flow freely and the women would laugh as the man drank. And in the bluish dawn, they would drive home in their cutters, exhausted but happy.

But it was not to be so, at least for Toussaint and his wife. Early one wintry morning, Willie James cried out in a howl of pain. In vain, they tried to console him but the clock that ticked off the hours told of their useless efforts. All that day the baby cried and by midafternoon his throat was raw and the cry had weakened to a dry rasping wheeze. They could hear the wind howling through the cracks in the mud-plastered logs of their shack, and that night the child they'd grown to love passed on. In the years that followed they would often wonder how their child had died so quick. There had been no autopsy and the questions that plagued their minds would remain unanswered forever.

That spring, Joe Taylor, the Indian Agent persuaded them to try adoption and the little two month old French boy that arrived to join their family bouyed up their hopes to the heights of ecstasy. They had suffered so much but the pain they'd endured only served to strengthen their devotion to Alice and Little Joe.

Toussaint and Mary Louise were now in their thirties but the years of sorrow they'd endured plus the depression made them look years beyond their thirties. They knew that someday life could be good if only they could keep going but just then they felt like they could chuck it all if it weren't for their children. With their children in mind, they struggled on.

The summer that ensued would be one they would remember. After the crops were in they had time to take long, leisurely fishing and berry-picking trips. At night they would sit around a small campfire and listen to the night life in the forest. But all too soon the nights became chilly and the morning dew was replaced by frost. It was time again for the harvest and the back-breaking work with primitive tools began. As usual, they hurried in their last few loads of grain as the first few flakes of winter fell. Soon the snow would come in torrents.

Nothing they did could have prepared them for what came next. Little Joe was showing signs of a fever so Toussaint hitched up Tom and King to the cutter and rushed their baby to the hospital in Elk Point, Alberta. They left him there and drove home late that night bundled up under heavy quilts in the cutter.

On the afternoon of the second day, Joe Taylor, the Indian Agent, drove up in his sleigh. He didn't smile as Toussaint and Mary Louise stepped out of their shack to greet him. In the back of the sleigh, they found the body of their little Joe. The pnuemonia had snuffed out his life and the ride home had frozen his legs and arms stiff. Silently, they set about thawing his legs and arms with warm water. The feelings of grief they'd forgotten returned in swells of emotion.

But, as always, time stepped in to help them shoulder the burden. At least, they still had Alice, but even so, the shack seemed empty and haunted by the happy shouts of children who once lived there.

Sometime during the winter of that year, the Indian Agent, had written the adoption agency again and it was a cold but happy spring day that found the little family on the platform of the train station at Elk Point awaiting a surprise. When the train arrived, a nurse debarked and with a curt nod deposited a two month old Ukrainian boy into the waiting arms of Mary Louise. Gordon had arrived. With the promise of spring in the air, they knew that the happiness that had eluded them so long would soon be theirs.

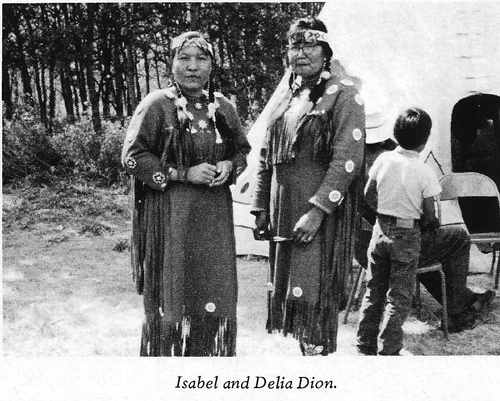

It would not be true to say that all was rosy from then on. What followed were years of hard times but the hard times were what held them together. A year after they'd adopted Gordon, a little boy was born to them. They called him Dewey. In the ensuing years, Bobby, Gabe, Delia, Isabel and Alphonse were born to them. By the time their youngest son was born, they were both nearing fifty and the years had etched themselves on the wrinkles of their faces.

Kehewin is a small reserve, approximately seven miles by seven miles. The lean years of the thirties had taught Toussaint well and he knew that in order for his family to survive, they must have more land. He began looking hard and the land he wanted, he found on the Frog Lake Reserve. He'd been Chief of Kehewin for sixteen years. His small farm had begun to prosper, yet his growing family forced him to abandon thirty years of work and head over Moose Hills to settle in Frog Lake where the wide open spaces of land would facilitate better opportunities.

But times had changed. Education was being pushed down the Indians' throats as a means of survival. No longer would a man have to virtually die of labour in order to survive. Many an Indian child's spirit died while the residential schools prospered. Toussaint realized that the time for a change had come and he watched as his dreams broke down like a light through a prism. His health began to fail and even before he was sixty-five he could barely walk without aid. The years of hardship they'd conquered together rushed back in torrents to invalidate them in the autumn of their lives.

Their children had all grown up and gone their separate ways. Only the three youngest remained. For the old folks, the race was nearly run and they quietly submitted to the will of the Creator.

She was in a strange hospital room at the Aberhart Memorial Sanitorium in Edmonton. That morning the sun had broken out in a glorious haze over the highrises of the city. Her youngest son, Alphonse was in to see her. She told him that her time was at hand. They talked for a long time that afternoon. She told him everything she never had a chance to say. Occasionally, she fell asleep. The little portable radio on the night table blared out current hits while he held her hand and she talked. Kenny Rogers and the First Edition mourned a wistful "Tell It All, Brother", George Harrison followed with "My Sweet Lord". "The end", he thought as he kissed her cheek and turned to leave. "I'll be home soon", she whispered. They both knew that she would be home soon but not alive.

The next morning (Feb. 2, 1971), the phone rang at their home in Frog Lake. "Hello, this is the Aberhart Memorial calling. Mrs. Dion has just passed away. She..." and the message was lost in the sobs that followed. The call that they had long been dreading had come.

Three years were to pass before Toussaint could follow his wife. During most of that time, he'd been bedridden. The will to live had long deserted him and he desired only the end. A heart failure brought him to the end on August 23, 1974. Three days later, they buried him beside his wife in the cemetery at the foot of St. Joseph's Hill in Kehewin. The cycle was finished, the story done. As the dirt thundered on his coffin and the grave filled up, the procession sang "Nearer My God To Thee". Long after everyone had gone, I, Alphonse, stood there staring at the two graves and for no reason at all, a phrase I had long forgotten leapt to my mind. "Hitch your wagon to a star", over and over again until someone touched my arm and we turned to leave.