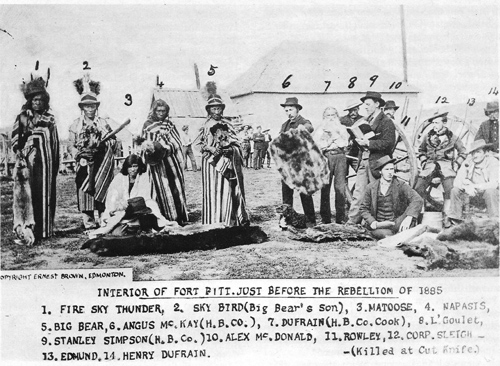

![]() From the official Mounted Police account of the North-West Rebellion as contained in John Peter Turner's "The North-West Mounted Police; 1873-1893, Vol. 2."

From the official Mounted Police account of the North-West Rebellion as contained in John Peter Turner's "The North-West Mounted Police; 1873-1893, Vol. 2."

By courtesy of The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Reproduced by permission of Information Canada.

On March 26 the day of the fight at Duck Lake far to the east, Cpl. R.B. Sleigh in charge of Frog Lake Detachment came to Fort Pitt with Andre Nault, son of Andre Nault who had stirred his cousin Louis Riel to action on the Red River in 1869. Young Nault had been arrested on suspicion, but sufficient evidence could not be adduced to lay a charge against him and he was allowed to go. On March 31 official word of the fight at Duck Lake reached Fort Pitt from the Indian agent at Battleford. Inspector Dickens immediately dispatched Cst. "Billy" Anderson with word to Agent Quinn, suggesting that he collect all the whites at Frog Lake and bring them to Fort Pitt or, if Quinn thought best, Dickens and his men would go out in case they decided to stay. Quinn replied that the Indians were friendly and that he was certain they could be kept quiet by liberal feeding.

A TENSE SITUATION

Extra guards were posted around Fort Pitt each night, and from that date on, though there were only 20-odd police on hand, preparations were undertaken for either a sudden Indian attack or a state of siege.

Chief Trader W.J. McLean, who had been given charge of the Hudson's Bay Company's affairs at For Pitt, Indian Agent Tom Quinn, and James K. Simpson and his assistant William B. Cameron of the Hudson's Bay store at Frog Lake, were familiar with the credulity of the Indians; they were well aware that all news from Riel would be accepted as fact. They knew there was already a taint of hostility in the air, that unrest was growing, that the ungovernable ethics of savagery were being preached by Wandering Spirit and Little Bad Man. Besides, Quinn, who knew Wandering Spirit to be one of the cruelest and most crafty Indians in the West, was mindful of the fact that he had more than once forestalled the plottings of this Cree war chief. No opportunity had been lost by either to give vent to a mutual, though suppressed, antipathy existing between them.

Trader Simpson had gone to Fort Pitt, and Cameron was alone at the little Hudson's Bay trading-post at Frog Lake. Since the defeat of Crozier at Duck Lake it was the general opinion among the Indians that the Chemoginisuk (the Mounted Police) could not stem the rebellious movement at any point, and at a gathering of whites at Delaney's house on the night of March 31st it was assumed that if an outbreak occurred, it would probably start with a clash between the Indians and the local police detachment.

Cameron suggested to Corporal Sleigh therefore that since his men were too few to afford any protection in the event of trouble, the whites would be safer if the detachment left for Fort Pitt. It was known that the Mounted Police were the preferred targets of revengeful Indians as a result of the Duck Lake fight, and all were relieved when Sleigh consented to go, although he was ready to remain if it were thought best to do so.

Quinn had previously advised Father Fafard to leave for Pitt with the others, but the priest had protested that they "should show they had confidence in the Indians, now that trouble had come." Thus the decision to remain rested with the missionary; otherwise all would have gone.

At early dawn on April 1, the day after Poundmaker's Crees invested Battleford, the little Mounted Police detachment left Frog Lake and vanished beyond the hills to the south.

Quinn called a council of the principal Indians that day. He wished to tell them not to be influenced by the tidings reaching them. To his surprise he found they knew more about the event at Battleford than he himself.

THE FROG LAKE MASSACRE

April 2, 1885 was destined to be long remembered in the log homes of the Saskatchewan. It was Holy Thursday, perversely chosen by Fate for the diabolical desecrations about to be committed. The Plain Crees, long in ugly mood, shorn of their accustomed freedom, reduced to abject poverty and recently exhorted to outrage by Riel's reassuring messages, had resolved to square accounts. Outwardly they had been unusually friendly to the whites the day before, and Quinn thought it advisable to humour them for the time being at least. Although he did not know it, he was already under close scrutiny by skulking Indians, who

evidently suspected he might try to follow the police to Pitt. In the small hours of the morning two Indians, Chaquapocase and Little Bad Man, entered his house and endeavoured to come upon him unawares in an upper room where he slept; but his Indian relatives - his Cree wife, her uncle and brother - all of whom had begged him to flee, intervened. Wandering Spirit called to him from the office below stairs to come down.

At the Hudson's Bay store were other Indians, obviously seeking possession. Fearing that the stock in trade might fall into their hands, Cameron had sent most of the ammunition with Corporal Sleigh to Fort Pitt; all that remained was a small quantity of powder in the bottom of the only remaining keg and perhaps a few balls scattered around the floor under the counter. This fell under the eye of Miserable Man, who jumped over the counter, elbowed Cameron aside and proceeded to gather it up; but Little Bad Man appeared and forced Cameron at the point of a rifle to deliver it to a mob of young braves accompanying him. Cameron, not wanting to touch the keg himself, called in a friendly Indian, Osowask, to hand it over. The young Indians then helped themselves to whatever they fancied.

Big Bear, who had returned from his hunt in the Moose Hills, shouldered his way in and with a wave of his hand said sharply: "Touch nothing here without asking for it."

He left again immediately.

Osowask then stepped out from behind the counter and towering over the young men, ordered them sternly out of the shop. Closing the door, he picked up a muskrat spear from under the counter and said to Cameron: "I will take this. I have no gun, and might want to use it."

Meantime other buildings had been entered and searched for arms and ammunition. In fact all arms belongin4o the whites were seized before the owners were out of bed. The war chief, Wandering Spirit, while in Quinn's office took three weapons from the wall. The Indian Department horses had been spirited away from the government stable during the night.

The ten white men of the village were now ordered to Quinn's office along with John Pritchard, his Scotch halfbreed interpreter. There, surrounded by a score of copper faces, the war chief hurled a scathing tongue-lashing at the agent. Who, he demanded, was at the head of affairs in this country - was it the government or the Company?

Quinn was a remarkably cool and courageous man. While he doubtless guessed that violence threatened, he had evidently steeled himself to face developments composedly. He ordered an ox to be slaughtered to satisfy the insistent calls upon him, but it only resulted in a momentary respite.

At the Hudson's Bay house Father Fafard accompanied by Father Felix Marchand, the Roman Catholic missionary at Onion Lake, sat down to breakfast with the Indian agent's nephew Henry Quinn, and the Hudson's Bay clerk Cameron. All agreed that the situation was becoming grave, even menacing. Over at Delaney's a number of Indians, as uninvited guests, took possession of the table and swept it clean of eatables. Soon afterwards young Henry Quinn, warned of impending danger by a friendly halfbreed, slipped away for Fort Pitt on foot.

So far, although firearms were much in evidence, there had been no voicing of the dreaded war cry, no definite forewarning of premeditated bloodshed. But as the hour of ten approached, many armed Indians, bedaubed with war paint, gathered around the little church where whites and halfbreeds of the Roman Catholic faith had assembled. Standing within at the back, facing the altar, were Big Bear with a gun beneath his blanket and Miserable Man. The latter was a large, coarse Indian with a face deeply pitted by smallpox, one who was fully as disagreeable a redskin as he looked. Big Bear stated later that he had gone to the church with the intention of interfering if there was any attempt to commit atrocities.

The whites and a scattering of halfbreeds soon occupied the pews. Then as the congregation knelt, there was a rattle of musketry at the open side door and a tall, lithe figure entered. Decked in primitive splendour, crowned with eagle plumes, his feathers hideously painted across the eyes and mouth with bars of yellow ochre, Wandering Spirit stepped to the centre of the church. Dropping on one knee, he held his Winchester menacingly erect in his right hand, the butt resting on the floor. With cruel eyes he glared at the altar and the officiating priests.

The fiendish butchery about to be enacted had been conceived in collaboration with Ahyimissees, the details of which were doubtless occupying Wandering Spirit as he knelt in mockery before the altar of the white man's God. This was the only interference with the service.

Father Fafard admonished the Indians to refrain from violence. The devotions were cut short, and all left the church. Cameron went to his store, followed by Tom Quinn who, while still cool and collected, nonchalantly remarked

that if they came through the day alive it would be something to remember.

Wandering Spirit had taken charge of the situation, ordering all whites to assemble at the house of Delaney.

Almost immediately after leaving the church, Wandering Spirit was seen in the doorway of the Hudson's Bay Company's shop. He ordered the shop closed, telling Cameron to join the other whites at the Indian Department and Mounted Police buildings. The Indians were then looting the latter. A friendly Indian, Yellow Bear, approached Cameron, saying he would like to get a hat at the store, and they started together in that direction. Halfway, they met Wandering Spirit, running with his rifle at the trail. Confronting Cameron, he ordered him back, but Yellow Bear answered for him, and they went their way.

Yellow Bear got his hat, and he and Cameron were leaving the shop when Miserable Man appeared with an order - doubtless Agent Quinn's last writing: "Dear Cameron - Please give Miserable Man one blanket. T.T.Q."

A shot rang out. Tom Quinn was the first to fall. Other shots followed. Miserable Man dashed out of the shop and reaching Charles Gouin, a halfbreed who was already wounded, placed his gun on the prostrate man's breast and fired. Big Bear rushed out of a nearby building, shouting at the top of his resonant voice: "Tesqua! Tesqua!"* But he might as well have shouted at the wind.

The friendly Yellow Bear led Cameron by the hand to behind the Hudson's Bay buildings, away from the shooting, and pointing to a group of Indians moving off, exclaimed: "Go with those women. Don't leave them." Cameron obeyed as a bedlam of shots, shrieks, the shrilling of the war song, the hoofbeats of galloping horses

and sharp commands in Cree broke forth. Walking about 20 feet in front of the women, expecting at any instant to feel the impact of a bullet which would spell his end, he reached the Indian camp and entered one of the lodges. Soon the ringing voice of Wandering Spirit could be heard through the camp.

"I killed Kahpwatamut (Sioux Speaker, as Tom Quinn was called by the Crees)."

Cameron found a valiant defender in the lodge, a friendly Woods Cree, William Gladieu.

Indian Agent Quinn and Charles Gouin had died side by side. Father Marchand had fallen while trying to reach his friend Father Fafard. George Dill, John Williscroft, an aged helper at the Roman Catholic mission, John A. Gowanlock, William C. Gilchrist who was Gowanlock's assistant, and Farm Instructor John Delaney were dead, their bodies strung out along the trail leading northward toward the Indian camp.

Of the white men who perforce had faced an implacable burst of savagery, William Bleasdell Cameron alone remained alive. John Pritchard became a prisoner and Louis Goulet another halfbreed, had been chased, but a friendly Indian had saved him. Mrs. Gowanlock and Mrs. Delaney were dragged screaming to the Indian lodges, to an unthinkable misery of soul and body.

In little more than half an hour the Frog Lake buildings, including the frontier church of the ill-fated Fafard, had been looted. After that, the inspired Wandering Spirit, supported by the silent pride of Ahyimissees, continued to boast and swagger before the plunder-filled lodges of Big Bear's camp, especially elated by the fact that he had killed his enemy, Kahpwatamut.

Cameron, helpless to save any of the others, was protected by Gladieu, who took him for greater safety to the lodge of Oneepohayo, a chief of the Woods Cree who against their wills had become involved with their kindred of the plains in an affair from which they would gladly have escaped. Urgently solicited by those who had been befriended by Cameron and the Hudson's Bay Company, Wandering Spirit gave orders that the young white clerk was not to be killed. Meantime a party of Indians had left for Cold Lake about 40 miles to the north. There, on the same day as the massacre, they took in charge H.R. Halpin of the Hudson's Bay post, and two days later brought him to Frog Lake. Cameron had previously begged that Halpin be spared. John Fitzpatrick of the Indian Department at the same point had been seized, but being an American, was comparatively safe - Americans were reputed to be helping Riel.

*Stop! Stop!

Soon after the killings, James Simpson, the Hudson's Bay Company supervisor in the Frog Lake district, drove in from Fort Pitt, where he had gone a short time previously on company business. Though he was at once made prisoner, Big Bear lost no time in visiting him and assuring him that the murders were none of his, Big Bear's, doing. Mrs. Simpson, a halfbreed, had escaped concurrently with Cameron.

John Pritchard the Scotch halfbreed interpreter now proceeded to perform a service which stamped him as a noble and unselfish man. History has passed him lightly,

but his name should live.

The two captive white women had become separated, each surrounded by yelling, blood-crazed Indians. Immediately after the sacking of the village, while Mrs. Gowan- lock lay in a frenzy of fear in the lodge to which she had been dragged, a little girl, Pritchard's daughter, entered to say that her father was in the camp and would try to help her. Soon afterwards the desperate woman was allowed to go to Pritchard's lodge where she found Mrs. Delaney: The kindly rescuer, who had been keeping close watch on the women lest they be victimized as he feared, disposed of all his available property, including his only horse, in order to gain possession of the two women in trade. Another halfbreed, the same Pierre Blondin who had recently come from Duck Lake and had been employed by Gowanlock, made a show of assisting in purchasing the unfortunate women by contributing still another horse, but it was soon proved his interest in the deal, which Pritchard frustrated, was purely selfish and discreditable.

The next day Big Bear paid the women a visit and told them he was sorry for what had happened, that there were many bad men in his camp over whom he had no control. A night later two Indians crept into the lodge and tried to gain possession of the women, but Pritchard intervened to prevent mischief, and henceforth guarded the lodge each night.

The Indians placed most of the bodies of their victims within buildings and applied the torch; one, Four-SkyThunder, was responsible for the burning of the church. All the cattle in the neighbourhood were rounded up; provisions had been taken from the stores and the several dwellings, and feasting, dancing and high revelry went forward day and night in the Indian camp.

Frog Lake settlement was practically wiped out. (At this writing it is an area of many little farms.)