ACCIDENTS AND INCIDENTS AT THE

ACCIDENTS AND INCIDENTS AT THE

HEINSBURG CROSSING

Like other such sites of river crossings, Heinsburg has been the scene of humor, mishap and tragedy. An incident during World War I, although not funny to the main character, brought forth a remark that was humorous. Albert Winkler, ferryman, went out to his land at Lake Whitney for spring seeding, leaving his wife to operate the ferry. The cable broke during that time of high water and floated downstream. Mrs. Winkler did not share the concern of others as to saving the ferry. She has been quoted as saying, "To hell with the ferry, save the voman!"

John and Mike Maksymuik, get out, with the help of neighbors, at Easter, 1942

A later humorous incident involved tourists crossing on the ferry. A lady commented to the ferry operator that it would be a nice job in the summer -- but what did he ever do in the winter? The story earned a cash award from Macleans magazine for Hugh McGladdery of Kitscoty.

Brett Naconce lands at Heinsburg, 1930's

In the early 1940's Ben Timanson had been hunting at Crane Lake with two other men. Coming back they had a load of birch logs and three buck deer. They took the meat home and three weeks later returned to get the truck they'd left on the north side of the river. The day that Ben and Cecil Sinclair went to Heinsburg, it was -38 degrees F and they were sure the ice was safe for the load. They got about two thirds of the way across, but the south channel was not frozen to the necessary thickness. The next day when Eby Walker went back with them they "sawed the river in two" and got the truck out. Knut Rinde's TD9 International cat, with cables, pulled it back to the north bank.

Mr. and Mrs. Mcllwraith, teachers at Fishing Lake, were returning home when their car stopped in flooded Irish Creek, at the Greenlawn picnic grounds. Eby took them to the river where they crossed on foot, on ice that was breaking up and moving.

Mrs. Mcllwraith and son

Once when Glad Horton was pushing mud away from the landing with his little John Deere cat the cable attached to the cat from the approach pulled through the drawbar before it was secured. The ferry began to move out into the river, towing the approach, with Walter Sawak on it, at the end of a chain. Its movement, combined with the current, pulled the approach down under the water. Walter, hanging on to a pike pole, was in great danger of drowning. John Nichols was on the ferry and immediately got into the rowboat, thinking he could rescue Walter. However he broke one oar and began drifting downstream. In spite of having only one hand he managed to get the boat to the north bank.

Leola Jones, about twelve years old, was also on the ferry, and since she was very familiar with its workings, Walter asked her to take the ferry to the south side, angling the opposite way from a usual crossing. This slowed the ferry and allowed the approach to come up in the water. In the meantime Cameron Isert, who had come to cross the ferry from the north side, drove to Nichols' where they got John's boat and motor. It was loaded into the half-ton and brought to the landing. The motor was put on, and started at first try, but by that time both ferry and approach had landed broadside to the south bank, and Walter was safe.

A number of lives have been lost through the years. The channel on the south side is deep with a fast current. In the 1940s, when the river was exceptionally high, a teenage boy from south of the river fell in and the body was never found. He had been attending Ellsworth School. A young man from the St. Edouard-St. Paul area went in swimming after eating and drowned.

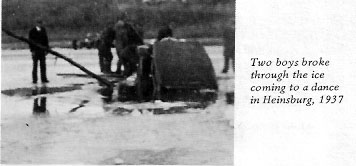

In 1943 a tragic accident claimed the life of Olive Walker, oldest daughter of Eby and Nellie of Greenlawn, and her friend Joan Harrington. They had attended a dance at Heinsburg and were returning home with two boys from south of the river, Vic Ketchum and Dick Schritt. When the ferry reached the south side the hook dropped into the approach and the cable was let down. The car would not start so the ferry operator went to help the boys. The vehicle was pushed back on the ferry, in the hope that once it got rolling ahead it would start. As soon as it was moved back, however, its weight caused the hook to lift from the approach. When the car did start the ferry was pushed out into the .river and the car carrying the two girls dropped into more than nine feet of water in the channel. Diving attempts failed because pressure would not allow the doors to be opened. Barney Johre went below to attach a cable so the car could be pulled out. Artificial respiration attempts were also of no avail. For a time after this, all but the driver in a vehicle had to walk onto the ferry. However, the policy of all remaining in the vehicle returned, and you seldom saw passengers getting out at the landing.

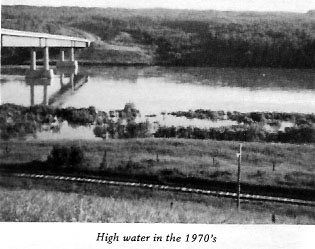

The bridge has eliminated these types of incidents. Crossing is no longer halted by high water full of debris or by ice, and there are no more long lineups while waiting your turn. People from far and near will remember lines that stretched back across the railroad track or further, and up around the bend on the south side. Once the Elk Point bridge was in you could often drive around that way quicker than waiting for the ferry. This traffic line-up happened on July 1 picnic days and on Sundays when people flocked to our lakes. But, human nature being what it is, we were probably taking the bridge for granted a week after it was put in use!