![]() by Alphonse Dion

by Alphonse Dion

Part I - The historic village of Frog Lake was approximately thirty miles from Fort Pitt. It was established in 1883 as a trading post and was also the centre of a Roman Catholic mission and sub-agency of the Indian Department.

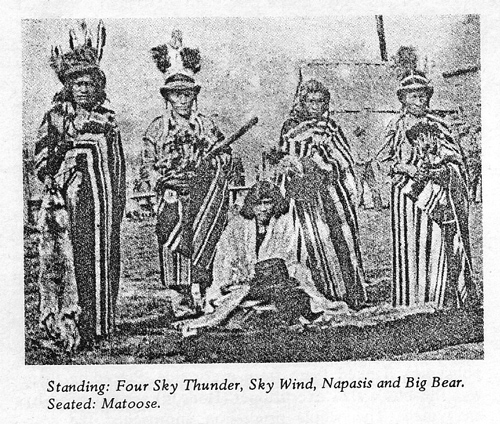

It was near the Woods Cree Reserve of Frog Lake that Big Bear and his people camped the following winter. They were in a state of near famine and even the twenty or so animals looked as destitute as their owners that February in 1885. Even game was scarce, and what little there was could not be hunted because of the deadly cold and the frequent blizzards. In order to survive they had to submit to the Indian Agent's dictum of "no work, no food." It was late February, and Big Bear, having capitulated, unhappily, to the Indian Agent's ultimatum, vowed he would stake out a reserve for his band when spring came.

On March 18, 1885 Big Bear chose the site at Dog Rump Creek, about ten miles east of what is now St. Paul, Alberta. Quinn attributed the move to the fact that he had begun to allow Big Bear's Indians to join other bands in the area. More often than not, Big Bear would relive his memories of freedom on the plains; finally he asked to see the commissioners one more time. But the outbreak of the Riel Rebellion smote out all else and Big Bear's freedom and authority began slipping slowly from his hands. He was a peaceful man, but the wisdom he'd been known for was being undermined by the more turbulent forces in his band, namely Wandering Spirit, Little Poplar, and Imases, Big Bear's eldest son.

Sometime during the winter Big Bear had promised that he would put up a feast if his tribe got through the hard winter. While his tribe was engaged in council on March 28 with the Woods Cree, Big Bear set out north toward Twin Lakes to trap and hunt for the feast he would hold during the Easter season. But, with his absence in camp, trouble was doubled. Big Bear would have been able to influence some by his authority, but his absence gave full rein to the extremists.

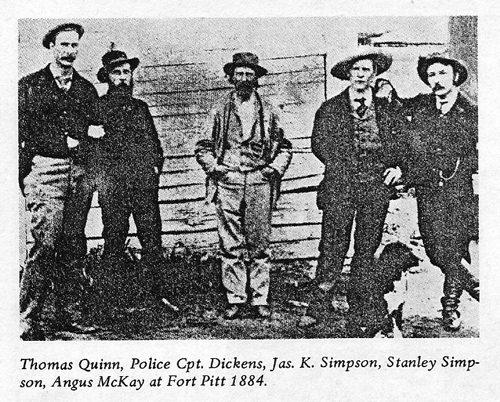

The news, which had excited the Indians two days earlier, reached the white population of the settlement of Frog Lake on March 30. Inspector Dickens informed Indian Agent Quinn of the uprising and advised him to come to Fort Pitt immediately. Quinn refused, saying the Indians were quiet and he could handle them. Nevertheless, the whites were asked to dispense with their small Mounted Police force at Frog Lake because it only served to agitate the Indians. Being a small force it would not have been very effective in case of an outbreak. The police were dispatched from Frog Lake on March 31, 1885...

After the massacre the bodies of some of the victims were later placed in the buildings and the whole settlement was burned to the ground.

Editor's Note - Part II of this article is described in the Pre-1910 Years in "An Account of the Frog Lake Massacre - by George Stanley."

Part III - Big Bear and his band packed up and headed east into Saskatchewan where the atmosphere was thick with the scent of hate and death. They reached Frenchman's Butte, where they stopped to hold a sundance. Runners were dispatched to check out Battleford. They returned with the news that it was teeming with soldiers. They stayed there long after the sundance had concluded, little knowing that Strange and his column were approaching Fort Pitt, some twelve miles away. News of General Strange's approach activated the Indians, who immediately set up battle positions on the hill by Red Deer Creek in Frenchman's Butte. Thick bushes ran on either side of the hill and if Strange attacked, he would have to come through the open meadow below the hill.

On the morning of May 28, 1885, the elderly general gave the signal to attack. They walked right into the trap the Indians had set for them. The Winnipeggers and the 65th marched behind General Strange and soon the single field gun began booming out the cry of death. The troop realized too late the situation they were in. Some of their men were wounded already. With no way to turn, they beat a hasty retreat. Middleton's reinforcements were probably on their way up the river from Battleford anyway, so they abandoned the battle site.

The clouds had been gathering that morning, and soon they made good their promise and it rained like it would never stop as the Whitemen retreated. The Indians did not pursue but were retreating in the opposite direction. Four days after the battle (June 1st), scouts under Steele returned to the battle site to find that the Indians had gone back the way they had come. Strange's troops returned the next day and scrambled over the battlefield, collecting souvenirs from the goods that Big Bear's band had abandoned. Steele and the mounted men of the column set off tracking the retreating band of warriors. Several times they picked up the trail only to lose it again. Still they pushed on through the wilderness. In their attempt they lost three men, and by then they had chased Big Bear all the way to Loon Lake, Saskatchewan. Encumbered by sick and wounded men they decided to abandon the chase and return to Fort Pitt. Ever present in their minds was the nagging fear that the Crees would turn and demolish their little force.

Middleton had already arrived by steamer when Strange and his men reached Fort Pitt. He took over the last phase of the campaign, the full pursuit of Big Bear. Meanwhile General Strange was sent in the direction of Beaver River, also to hunt Big Bear and his captives. Middleton set off on June 3 with a force of 225 mounted men, 25 artillerymen with a Gatling gun, and 150 men from infantry riding in wagons. Colonel Otter marched north to Turtle Lake and directed Irvine to move to Green Lake. The four columns would thus form a series of barriers, east or west, for. Big Bear and his followers, should they try to break and run.

After fleeing through deep muskeg and his band splitting and scattering, Big Bear surrendered on July 2, 1885. The old chief, evading all columns sent to intercept him, by turning in his tracks, travelling almost alone and covering his trail, made his way to Fort Carlton, where he gave himself up to Sergeant Smart of the Mounted Police. He was accompanied by a young boy when he gave himself up to the Whitemen. Thus, Big Bear was given a prison sentence on the charge of treason-felony. The remnants of his band were then merged with other bands, thus destroying the principal nucleus of Indian agitation.

Part IV - The guard room at Fort Battleford could not accommodate all the prisoners. With almost a carnival air the men in charge set about converting a stable into a temporary prison. Of the fifty-four men confined, seven received prison terms, and eight were sentenced to the scaffold. Six of the eight prisoners sentenced to die were members of Big Bear's Band.

Eight hempen .ropes hung in readiness for the task at hand on the morning of November 27, 1885. The platform of the scaffold stood ten feet above the ground and was reached by a stairway. Enclosing the trap was a railing. It was almost eight o'clock in the morning. Grim silence fell over the Indian students of the Battleford Industrial School who were brought in that morning to witness the event. Some of the students were direct relatives of the doomed men on the scaffold, yet they contained their smouldering emotions behind impassive faces. A squad of N.W.M.P. marched up to form a cordon at the foot of the scaffold as the doomed Redmen ended their last chant of death. Their hands were tied behind their backs and policemen flanked them from every side. Preceding them was the black clad executioner (Hodson) accompanied by clergymen. The whole procession approached the scaffold. The policemen stepped aside and the Indians mounted the stairs to eternity. They stood in a row before the ropes; eight men about to die for the sins of the Red and White. Eight men who never understood the difference between death by the bow and arrow and death by the noose. They were given ten minutes to say their final words while Hodson strapped their ankles to prevent escape. All but Wandering Spirit, bitter to the end, spoke briefly.

Apischascoos' speech before dying: "I wish to say goodbye to you all, officers as well as men. You have been good to me; better than I deserved. What I have done - that was bad. My punishment is no worse than I could expect. But let me tell you that I never thought to lift my hand to a Whiteman. Years ago when we lived on the plains and hunted the buffalo I was a head warrior of the Cree in battle with the Blackfoot Indians. I liked to fight. I took many scalps. But after you, the Redcoats, came, and the treaty was made with the Whiteman, war was no more. I had never fought a Whiteman. But lately we received bad advice; of what good is it to speak of that now? I am sorry when it is too late. I only want to thank you Redcoats and the Sheriff for your kindness. I am not afraid to die. I may not be able to in the morning so now again I say to you all - goodbye! How! Ekosanih!

Too soon the time had come. Black hoods were lowered and ropes adjusted. The priest lifted his hand in benediction as the iron grated and the eight bodies shot through the trap. The monstrosity of the event the audience had come to watch sickened them; some turned away. The Indian children of the Industrial School clutched one another. Some let out involuntary sobs for the braves they'd come to admire, now strung out like puppets in a ghastly marionette show.

It was all over. The last of the rebel spirits had been smothered. The government had the Indians under control once again. They had hung the rebel Indians to show what would be done to anyone who dared rise against the Government; since then they have led the Indians around on a string by their noses. The entire cost of the Northwest Rebellion was five million dollars.

The eight men hanged for their part in the uprising were: 1. Wandering Spirit, for the death of T.T. Quinn, Indian Agent. 2. Pahpahmeekeesick (Walking the Sky), for the death of Pere Fafard, OMT R.C. Priest, who had fathered the boy as a youth. 3. Manchoose, for the death of Charles Gouin, Quinn's interpreter. 4. Miserable Man, for the death of Gouin. 5. Nahpase (Iron Body), for the death of George Dill, free trader. 6. Apischascoos, for the death of Dill. 7. Itka, for the death of Payne, Farm Instructor of the Stoney Reserve, south of Battleford. 8. Waywanitch (Man without Blood), for the death of Tremont, rancher out of Battleford.