![]() MOHAMMED (ANDY) HAMDON

MOHAMMED (ANDY) HAMDON

I was born in Lebanon in the year 1904 and remained there until 1924 when I came to Canada. In the old country the influenza struck during the 1914-18 war. It was terrible! Within one week my father was gone at the age of thirty-seven, along with my grandmother and my brother and sister, who were very small children. It hit so suddenly, and the death toll was so great. More people died with the 'flu than were killed in the war.

When I decided to leave for Canada I went to Paris, where I spent two months, and on August 10th, 1924, I landed in Halifax. In Winnipeg I was met by my cousin, Alley Hamdon, and I remained there for two or three days before coming out to Edmonton. I went to work in my cousin's store at Fort Chippewayan, commonly called Ft. Chip. I worked there for a year and a half and returned to Edmonton. I couldn't speak much English but had learned to translate some English writing into my native language, although couldn't read it in English. Someone nicknamed me "Andy" and I am still called Andy Hamdon.

When I came back to Edmonton my cousin bought a horse and buggy for me, purchased some clothing and other goods (in fact anything that would sell), and I became a peddler. He took me to Strathcona Road and told me to travel south and stop at every house I came to. That first trip lasted about ten days; then my cousin told me, "If you don't like that (peddling) come back north with me." I decided to try peddling a little longer. My travels took me to a small town called Lougheed where I met a nice family, very hospitable, and I stayed with them overnight. I wanted them to keep my horse for me while I went back to Edmonton, but I didn't know how to make them understand that I wanted to go to Edmonton to see my cousin. Finally the lady of the house wrote on a piece of paper "You want to go to Edmonton." I nodded yes, and by signs we came to an understanding. They kept the horse for me. I went back to Edmonton and told my cousin I did not want to go back north. I peddled around the Edmonton area for two years, 1926 - 28. I went back north again, this time to Black Bay (Radium City) in the North-West Territories. This was in the fall of '28, and I operated a store there. My customers were mostly Indian and Metis.

In 1929 I went to Fort Norman, where another cousin had a store. At that time the country there was nothing â no cars, no planes and no skidoos â nothing like it is today. The only white people were the police and Hudson Bay Free Traders. The mail was delivered by horses and sleighs and by dog team. Feed for the horses had been spotted at cabins every so many miles apart. Starting at Fort McMurray the route went down north including Ft. Chip., Ft. Resolution, Ft. Smith and all the way down to Ft. Norman. I believe it went on to Aklavik but I have no knowledge past Ft. Norman. Christmas Day the mail was brought in by plane. The plane could not land so they dropped the mail. The bag was so heavy that when it hit it made a hole in the river about two feet deep. I remained in Ft. Norman until the spring of 1931. During that time an epidemic (I think it was 'flu) struck the Indians, and for the second time in my life the horror and mourning of sudden death was all around me. The natives died like flies; the living could not keep up with burying the dead, and many were buried in the clothes they died in. One custom that seemed heartless to me was when a man gave his mother a box of matches and a blanket and left her in the bush. When questioned by the police he remarked, "She is no good; she is too old, so I left her." The police found her in time to save her life.

I left my partner in Ft. Norman and, accompanied by a Frenchman and a Swede, headed down the McKenzie River in a small boat (skiff) powered by a little kicker, that is, a little gas engine. Not to be caught unprepared, we took three kickers with us; which was fortunate, because the first day the kicker broke.

Going down the Mackenzie, ducks were plentiful. We shot enough for eating, going ashore to camp and cook the ducks. In about three days we came to Slave Lake. We had to enter the lake, but our passage was blocked by an ice jam. We waited three days, and if the Frenchman hadn't come prepared with a little fly-hook to catch fish, we would have had nothing to eat. There was a town not too far away, but we were blocked from it by the ice jam, and they could not see us. After a three-day wait the Frenchman and Swede left me with the boat and walked five or six miles up river, hoping someone from the town would see them; but no one noticed. However, they were resourceful men; after walking another two miles up river, they took a spruce tree with limbs on it, pushed it into the river and guided it across. From there they walked into town, where they bought some buns and other grub, and a boat brought them back across the river. The next day the wind changed and shifted the ice, so we could go through with the boat.

We went to the town, where I went to the Mission and asked the Sister for some bread or buns. She thought we were starving and gave us some, then told me to come back for more tomorrow. Next day we went back and she gave us lots for the trip. The Priest gave us a drum of gasoline for the kicker, and we made it to Ft. Chip. I stayed there and ran the store for my cousin Alley, while he went to Edmonton for stock.

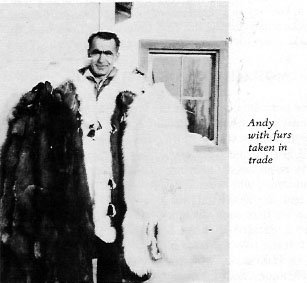

He came back in September, and I set out for Stoney Rapids, Saskatchewan - a two hundred and fifty mile trip on Lake Athabasca - where I opened a store of my own. There were only two police (very nice men), a Hudson Bay store manager, and me. My customers were Chippewayan Indians, and I traded for furs - no money.

Once a year I made a trip from Stoney Rapids to Ft. Chip. with a team of five dogs to sell my furs and get supplies. This trip, of two hundred and fifty miles one way, took two or three weeks. There were no houses on the way, so I slept in the bush with my clothes on. I worried about timber wolves, so I made the dogs lay down in a circle, and I slept in the center for protection. In the morning I made a little fire to make tea. It was so cold that when I tried to cook meat it would freeze on one side, while cooking on the other. The snow was too deep to find wood to make much fire. It was a tough life.

One spring, in May, I came into Ft. Chip with my furs. Lake Athabasca was still frozen over solid. My Indian helper and I loaded over five hundred pounds of supplies on two sleighs which were under a skiff. These sleigh loads were pulled by ten dogs. We set out for home across the ice. One morning, shortly after sunrise, the ice in front of us divided. The dogs jumped from the ice to the water. The skiffs lashed to the sleighs kept the sleighs afloat and the supplies and us, dry. The dogs swam the open patches of water, but each time they came to a piece of ice we had to pull them back into the same hole so they could scramble up on to it instead of going under it. We were heading for the Island. At last we saw an open patch of water about fifty feet wide. My partner said, "If we can cross this we will make it to the Island." We made it across onto the ice. One dog went down, then the second went down. The Indian said he would pull them out. I just started to say, "You'll get wet" when the ice gave way under his weight. He got wet! It took us all day to reach the Island; but we were safe and camped for the night.

The next morning, after we loaded the 1200 pounds of supplies onto my sleigh and skiff, the helper headed back and made it to Ft. Chip. I set out across the ice for home. When I came to where a crevasse had opened in the ice I got some water, made a little fire using wooden boxes, and made a meal on the middle of the lake. I slept on the sleigh and the dogs took me safely home.

In 1939 I went out to Edmonton for supplies. I flew from Stoney Rapids to Prince Albert and took the train from there. I was in Edmonton when the war started in September. I got my supplies and went back north by way of Ft. McMurray, taking the McGinnis Brothers' boat (they were freighters) from there home to Stoney Rapids. Caribou were as thick as flies, so we had lots of meat to eat.

I hadn't heard much about what the war was doing to prices, but the Hudson Bay manager had been kept posted. In July of 1940 one of the police was helping me take stock. In came the Hudson Bay manager and said, "Would you like to sell out?" I simply froze! I couldn't speak and the policeman, who was a very nice man (as I said before), said, "Sure." The Hudson Bay manager immediately handed him a draft. I thought he was joking and didn't realize what was happening, but the policeman put the draft in his pocket and tossed him the keys. I had almost three hundred beaver furs and over a thousand rats. The policeman told his interpreter to load them on the police boat. He took my eiderdown and pillow and put them in the boat. I still seemed like someone in a daze. He put me on the boat and took me to the police barracks. He stamped all the beaver and shipped the furs. He went to the vendor's and bought a bottle of whiskey, cooked a good meal, and told me to get out. At five o'clock in the morning he put me on the boat and I waved goodbye to stewed rabbit.

I went to Edmonton and bought a Model A Ford. I wish I had it today. I went out into the country and bought a little fur here and there; then I went back to Edmonton. I bought a house and little store on 52nd. Street in Jasper Place. At that time Jasper Place hadn't joined up with the city of Edmonton, and there was no gas or water. I bought the house and store for $2500. I could have bought as many lots as I wanted at $10.00 per lot. I had enough money to do so, but I didn't take advantage of it. If I had I could have made a million when prices went up. Bread was 34 a loaf and milk or a bottle. I couldn't stand that kind of business after the $1,000.00 per day fur trade I had handled up north, so I sold the business at a $500.00 loss and went back to buying furs here and there.

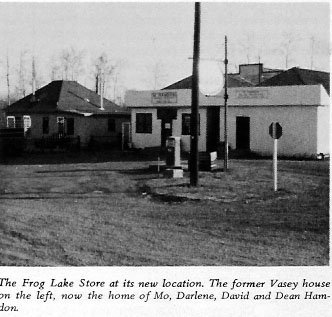

I came to St. Paul, where I met Josephine Kitz of Myrnam. In August of 1941 we were married and went to Lac La Biche, where we started a mink ranch. We stayed with the mink for three years, not long enough to make a success of it. For some time I had known Alex and Kahlill Tarrabain, who owned a farm at New Norway and a store at Frog Lake. In 1944 they wanted to sell, so I made a deal and bought both the farm and the store. On January 15, 1944 we moved to Frog Lake.

This again was a different kind of life. It was a country store, situated just off the south edge of the reserve on the hill east of Frog Creek. We had living quarters upstairs above the store. An elderly couple, Mr. and Mrs. Harry McDonald, lived nearby and ran the post office in their home. Our customers were natives, Metis, and whites. Our heating system was a big gas drum that burned big sticks of wood, which we bought from the Indians and had sawed by a buzz saw. At first we used coal oil lamps, but later we installed our own lighting plant. We worked seven days a week and were "on call" at all hours.

There were a hundred and seventy-six Indians on the reserve in 1944, and some lived in tents even in winter. John Horse was chief. I had learned some Cree while in the north in order to wait on customers, and this helped me a lot. There were no phones, and we had our freight hauled from the railroad in Heinsburg, some ten miles away. In summers horses and wagons, and in winter sleighs were used. Later we bought a small truck. This made things much easier.

We soon became part of the community; we joined the community club and took part in the social activities. We liked the Indians and got along very well together. Later, when the Indian Hall was officially opened, Fred Horse, who had become chief, asked me to be Honorary Chief for. the day and cut the ribbon. My niece, Fatima Coutney, acted as my squaw. Another event we went to in their hall was a box social. They danced the Red River Jig, and we square danced with them.

The nearest R.C.M.P. detachments were at Onion Lake (with one man) and at St. Paul (with four men). Our place was always open to them, but when they were needed between their regular patrols, someone usually rode horseback to get them.

Because there were no phones, Josephine stayed in Elk Point several days before Emily and Mo were born. Dr. Anne Weigerinck, who had a small office in Heinsburg, came from Elk Point once a week, and an optometrist visited Heinsburg once a month.

There was a short supply of goods during the war, and the government issued people a coupon book; coupons for sugar, jam or other sweetening, tea or coffee, and meats. Only small amounts of these commodities were allowed each customer per week, and we had to tear the coupons from the book with each purchase and send them in. Each coupon was dated, and could not be used ahead of the date.

Left: Emily, Josephine, Mo, Andy, Faye and Jeanette.

We had been here about eight years when my nephew, Wadia Coutney, came from the old country to work for me, later bringing his family out. We left Frog Lake to make our home in Edmonton, leaving Wadia in charge of the store until he left, and our daughter and her husband (Jeanette and Jerry Russell) took over. Presently our son Mohammed (Mo) and his wife Darlene are back at Frog Lake looking after things there. Our second daughter, Emily, married Art Reid and lives in Victoria. Faye is home with us, working in Edmonton. We have six grandchildren.

I felt a bit sorry for myself back in 1940 when I left Stoney Rapids, but it was my lucky day. I had to come out to meet Josephine, and we are happy together. We went to the old country for a four-month visit in 1962. I wanted to show my wife places she had never seen, so we stopped over in England for a week; and in Paris for five days; then we went on to Germany, and from there to Geneva, Switzerland. We visited Madrid and watched a bull fight; to us it was torture and not a pleasure to watch. We went to Rome and to Vatican City, where we saw the Pope, and visited the catacombs. We stayed two weeks in Egypt, and went under the pyramids, where we saw the mummies and a coffin made of pure gold for a king.

We flew from Egypt to Damascus, and then went back to Beirut. We were in Beirut for ten days before we let my family know we were there; we wanted to look around on our own. We spent a day at the Gaza Strip. That was a sad sight; people were really starving and no amount of money could relieve their suffering for any length of time. I had $60.00 in my pocket and gave it all. It wasn't even a drop. Tourists were almost mobbed by those weak, hungry people. When I sent word to my brother that we were in Beirut he was there within two hours, and we had a wonderful reunion with the family. The country was much changed, much more modern than when I had left in 1924. We made one more trip back to Lebanon in 1972. We have also attended the Expositions in Japan and Montreal, and have visited Hong Kong and Hawaii.

All our lives we worked hard and put up with many hardships; now we are taking life easier. Canada is my home. I am a Canadian.