SA-WE-PAH-U

SA-WE-PAH-U

as told by Solomon (Sa-we-pah-u) Delver

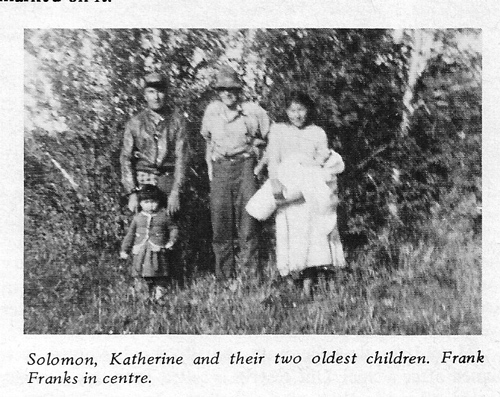

My father's Cree name was Sa-we-pah-u. He used to tell a lot of stories about away back, and about what he did when he was a young man. He told about hauling freight from Edmonton to Fort Pitt; like the story he told about pulling barges up river when he was very young, it is true for that is the way he told it to me long after. Like when Mr. Frank Franks and his brother, Billy Franks came up to this area; that was a long time ago. I think when they first came to settle here my dad was one of the first to see them when they arrived at Lea Park.

When my dad and his family saw them, these first White- men, coming into the west to this side of the river, they were having a dinner where they had stopped. This is what my dad told me many years later. He couldn't speak a word of English himself or couldn't understand a word the Whiteman said and they could not speak or understand Cree. He made signs to these white people to understand him. They actually learned to understand one another.

They used to make all kinds of deals, haying and other kinds of business-like deals for brushing by hand with an axe and picking roots for a lot of days. Later more white people came; early settlers like Mr. and Mrs. Ole Lunden and Mrs. Barstad. He used to tell me he got to know all these, the Bristows; Old Man Bristow, Frank Bristow's dad, and all the local people up in here. He used to go out brushing and stooking and threshing for them to make a living.

The Indian people used to trap, hunt and fish. They never asked the Government for assistance. They went on their own trying to make out for themselves. They tried to cultivate some land so they could grow some potatoes and other things for food. I know they cut a lot of posts which they traded to the white settlers.

Later they got some assistance when Alex Peterson was teacher and sub-agent on the Reserve. They weren't getting very much, not like the cheques we see people getting to-day. Them days they used to get so many pounds of rice, so many pounds of flour, so many pounds of salt bacon. They were given tea, matches and soap which they could use. That is what Dad told me they used to get. There are a lot of other things written; I haven't got them with me to-day but they are written some place. Later they used to haul wood to Heinsburg after it became a town. They didn't get very much money for the wood they hauled but it helped out.

When I was a very small boy, I don't know how old I was, I was sent to the Roman Catholic Residential School at Onion Lake. I was there for twelve years. My dad had sent me there to learn to understand the language of the white people. It was hard for me to be brought up as an orphan. I stayed with the nuns; they told me I am really a Roman Catholic which is how I was brought up. I used to ask a blessing before every meal I had. I used to go to Church in the evenings and in the mornings to the service in the Chapel before breakfast. I remember all these things when I was in the Residential School. It was hard far away from home, but it was the only way in which I could understand the Whitemen. I learned to understand a few English words, but not too much, although I studied for that many years.

Then the days came when the Anglican Missionaries set up their missions. There were 332 residential schools built right across Canada for the Native people. I found this out from my dad when I came back to the Reserve. I learned a lot of the things my dad had experienced from things he told me.

This is what my dad told me about when he surveyed the Reserve in 1917. He had put in an iron peg on every corner which is marked with a crown and I.R. for Indian Reserve and he put pins, which he marked with I.R., after every mile around the reserve.

He told me that there are actually three reserves, each named after a chief. One reserve is called Tus-tuk-ee-skwaks named after the chief who signed the Treaty with Queen Victoria in 1876. The other day I realized that the new school for Native children is on it. I would say that when my dad showed me we started where the west end of the school is. The next chief was named Puskiakiwenin. There was another chief in Frog Lake named Na-pa-heos. My dad told me these are the three chiefs who signed the Treaty in 1876. On the south edge of the Reserve is a sign which says Unipouhoes but that is not right. It was Unipouheos' father, Napaheos, who signed the Treaty.

I have told you my father's name was Sa-we-pahu; he was eight years old at the time of the Rebellion in 1885. He was the son of Na-skok-ases, his mother's name was Keechee-kew. He had four brothers; We-ap-pan-otum was twenty-three years old at the time of the Rebellion, Nap- wan was eighteen, and Mo-ne-kew was four. Native children were not baptised in those early days so they had to name them themselves or an old woman would name them. This is the way my father told me that it was put in the records.

After the Agency had been transferred from Duck Lake, in Saskatchewan, to Onion Lake Agency, they transferred the records from Saskatchewan to Alberta. When the Inspector, which is what they called the original Superintendent of Indian Affairs, came with the Indian Agent they asked my grandfather to name his children. That is when my father was named Sa-we-pah-u. Later the Indian Affairs gave him the English name of Joe Delver. Even myself, I found on my baptism certificate that my name is not Solomon Delver. It is Solomon Edwin Sawepahu. My sister was named like my father, Emma Sawepahu; she is Mrs. Fred Fiddler now. There was another sister, Susan, who was married to Domonic Berland and I had another brother, Pierre Sawephu. He died on the Frog Lake Reserve when they had small-pox a number of years ago. I don't know when it was but my dad told me about the flu that destroyed many native people. The local people know when it was.

But to get back to the story according to my father. - The Inspector asked this other son what his name was, it was Mo-neh-kew; then there was Napwan, he was given the name of Michael Fryingpan by the Agency. Then they called We-ap-pan-otum, Thomas Faithful, and Monehkew was named William Delver. That is the way they were stated in the records of my grandfather for my father.

After I came home from the residential school and after I had grown up to become a young man I went harvesting in the fall, stooking and threshing. I became a laborer and worked for the people around the local area and I also worked south across the river. That is how my dad brought me up. He had farmed about seventy acres with Fred Fiddler. He told me a lot of his experience with farming but I didn't know how to use it; I was too young.

I learned to smoke when I was almost eighteen years old. It was when I was harvesting at Hines' that I drank a little bit. That was my first drink. I was nineteen years old and I didn't know anything about drinking. The next day I didn't feel so good. My dad also hadn't known anything about liquor. The first liquor he had tasted was when he was working for the Hudson Bay Co.; working in water while hauling freight from Battleford to Edmonton with rafts. Later the Indians learned to make their own moonshine, called "moosemilk" by the white people, and made out of oats, yeast cakes and some potatoes. That is how they made their booze.

In 1946, on May 3, I married Miss Katherine Desjarlais. Her parents names were Pete and Mary Desjarlais from the Fishing Lake Colony. We brought up a family, our oldest boy we named Harvey, then there was Dennis, Sylvia and Clifford.

When I became a councillor for the Reserve I really fought for my native people. I tried very hard to find out why our old grandfathers and fathers couldn't think or talk for themselves; why they couldn't talk to the Indian Agent who was the only one they used to see. I used to interpret for George Stanley and Old Man Ne-pah-kua-tow. I know these things I have told in this story because it is what these old people told me. I spent much time with them and with my dad. I had to because of the age at which I was brought up alone. I think I was about one year old when my mother died. Her name was Angeline Moyah. I do not know her mother's name but her father's name was We-soo-paek-see.

We lost three other children in a fire on November 17th, 1971 when our house was destroyed. One year later another family lost three children in a fire. These were bad times for the Reserve and especially for us parents. Since then I have been trying to manage myself and I couldn't manage myself until I had received my sobriety. I learned a lot from the experiences of my dad; from the things he told me, but he couldn't tell me about drink. I taught myself. I had to find out for myself!

Now, many years after coming home from the Residential School, I have thought to myself that while there I was not taught anything about the kind of life I would have to live on the Reserve. I wasn't taught anything about liquor such as beer, wine and whiskey. I wasn't taught anything about drugs; about sniffing; about what would happen when I got out from school, and now I face these problems.

We have a new school now for the Native children. We are trying to work toward an understanding of how to bring up our children and grandchildren for the future. We sent our children from the Reserve to the public school. There are still Native children attending the Heinsburg School.

I don't know what the Native people are going to do. It is up to each family to make their decision. I know this one thing; that still to-day we are not learning our kids anything at school about the main point of life. Life is the life of liquor problems for the Native People. The thing I want to see is that the children are taught for the future: how to handle their drinks like the White society. The white people do drink but they know how to handle their drinks; but the Indian does not. It is about a thousand years ago since the white society have made their drinks. Actually it is, say, about a hundred years since we Native People began to drink.

The early Native People had a sobriety; a sobriety in which they used to supply their own food. They had made their own living before the Whiteman came to Canada. They, the Indians, knew what to do for their sicknesses; they had herbs, some of which are used yet to-day. There is this thing I know about myself; I was badly boozed with alcohol.

I have been thinking about our great chief Tus-tuk-eeskwahs. His grave is all alone on the south-side side of Frog Lake, toward the south side of Fishing Lake Point, a little on the west side of the shore on the west side of the hill. That is where I still remember that my dad pointed out to me when I was very young. That is where our greatest chief was buried, all alone up there. It has not been looked after but the rocks are still there.

I have been looking forward to getting help from the people, to look after our cemetery, and also from the Indian Affairs, but no help has come yet. There are quite a number of graves in the Reserve cemetery but they haven't been looked after, not like I see in the white society. They are looking after their graveyards in the right way, but us, it seems we forget!

Even my dad's grave, I only put a pin in there and there is nothing which I put in to mark my mother's. I know that soon the graves of our early people will be gone. The grass will grow over them and they will disappear and the younger generation will not know anything about them, about who lies in each grave or where the grave of Tus-tuk-eeskwaks is situated.

I have told quite a bit that my dad told me. He also told me that a long time ago the Indians had received a steam engine with a sawmill so they could try to saw their own logs. The logs had not been sawed for centuries and there should be a lot of lumber on the Reserve. They took this back and forth between the two Reserves, Kehewin, which is the name of the Long Lake Reserve, and Frog Lake. Also they took it to Cold Lake and Legoff. It would have been better had they received a team of oxen when they first started for they did not know how to run the steam engine and sawmill.

My dad and other early native people received six cows to start with and they managed to make some kind of living for themselves. They had never grown any grain or had any machinery at all like we see to-day, but they had a mower and rake and a hay slough to manage for feeding the cattle through the winters. It seems to me that those days were kind of dry and the sloughs dried up: now they are hay meadows. Ever since then they had raised a few head of cattle at each home on the Reserve through the old people.

This year, in 1975, Fred Fiddler, Harvey Delver, William Berland and Dave Silliman resurveyed the Reserve and put new pins all around. During this survey they found a tamarack peg that was in a muskeg and you can still see I.R. marked on it.