ADOLPHUS FRYINGPAN'S FAMILY

ADOLPHUS FRYINGPAN'S FAMILY

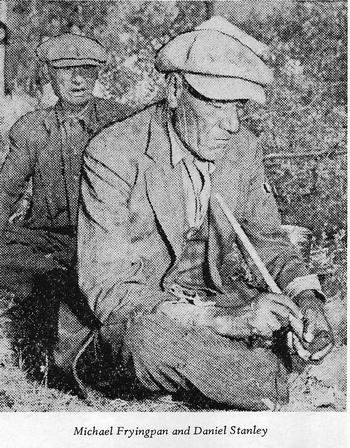

I am Adolphus Fryingpan, grandson of Michael Fryingpan, whose Cree name was Napwin. His father was Naskokasees. I don't know why, but the White people called Naskokasees "Old Bum." I have been told that he lived to be very old, more than 100 years, when he rolled into a campfire in his sleep, and that is how he died.

I was born in 1928 on the Frog Lake Reserve. My mother was Eliza Fryingpan. My mother and father, Jimmy Cheeskum, both died when I was very young. I was about three years old when I was sent to the boarding school at Onion Lake where I stayed until I was twelve. Since then I have always lived at Frog Lake and was raised by my grandfather, who became more like a father to me; and his children, Joseph, Johnny and Isobel, were like my brothers and sister. Isobel married and her name became Isobel Gadwa; then she went to live at Long Lake, which is now called Kehewin.

Napwin was one of the older men of the reserve. He was born before the 1885 uprising. He taught me the Indian way of life, to hunt and fish. He taught us that it was wrong to kill more than we needed, and wrong to destroy the wildlife and trees, so he didn't do much farming. The Indian Department gave him and the other older Indians several head of cattle, a mower and hay rake, and he raised enough horses to use on the machinery, so we could put up enough hay to feed the livestock in the winter. He tried to put up as much hay as he could because he could get a permit to sell what he didn't need to the white farmers. He usually got paid $2. to $2.50 per load.

In those days the Indians were not supposed to sell anything off the Reserve without a permit, which they got from the Indian Agent. That law was often broken and sometimes beef, deer meat, fish or even a live calf was hidden on the bottom of the wagon box under blankets or hay, and sold or traded to the mon-ee-as (whiteman). The Agency and police didn't notice this unless someone told. They did notice and try to stop the white people from trading us liquor. Permits were given so we could sell dry wood. We were not allowed to sell green wood, but most springs there were enough bush fires to make plenty of dry wood. There wasn't much welfare then, but the sick and old people were given rations. We trapped and sold furs to the local stores, so Grandfather earned enough to raise his family without help from the Department.

When I was nineteen I married Louise Stanley, who was also raised by her grandparents, Daniel and Eliza Stanley, and she grew up with their children: Angus, who married Maryann Abraham; Annie; Richard; Harriet, who married Johnny Fryingpan; and Jeanette, who was the same age as Louise, and who now lives at Rocky Mountain House. Louise received her education at the Anglican Day School on the Frog Lake Reserve. Her teachers were Alex Peterson and Mr. Hunt.

I had always been raised as an Indian, but after Grandfather died and I married, things changed for me. I had always been called Fryingpan, but then some people thought my name should be Cheeskum, but the Reserve was, and is, my home. Before I tell more about my life I want to say that I am not trying to judge the law of the Reserve, whether it is a good law or not, but I could not understand it. When Louise and I got married in the Church I was told that I was not a full-blood Indian and could not receive the Reserve privileges, which I had always thought were my inherited right. I tried very hard to get my Indian citizenship, but was not successful. I do not understand why our oldest son is the only one of our children who has a Treaty number and gets the Reserve privileges.

Thomas Faithful, Joe Abraham, Adolphus Fryingpan, Thomas Quinney, Joe Fryingpan

I am glad that I was allowed to live on the Reserve and raise my family here. Louise has helped me a lot. She has her Treaty number and shares her Reserve privileges with me. In her name we could get permits to sell hay and wood. She could get a hay field and use the band's mower and hay rake, and pasture our cattle and horses on the Reserve. Our children went to the Reserve schools until we decided to send them to the Heinsburg school.

After we were married we had to earn a living, so we went to work for the farmers; sometimes we received a cow for wages, so we could raise some cattle. Louise helped me put the hay for the winter's feed. One farmer we worked for was Frank Franks, who had always been a good friend to the Indian people. Louise went with me to work and helped brush, pick rocks and stook.

For six years running we camped during the summers at Franks' to help them put up hay. Louise drove the team on the rake while Frank and I stacked. Frank and his wife Grace watched the sky for rain clouds. They didn't like the hay to get wet so the more it looked like the rain the faster we tried to work. Sometimes we stacked as many as twenty loads in a day. They tried to get it in the stack as soon as it was cured enough to keep. Hay wasn't baled in those days, it was forked loose into the hayracks, hauled in by team, and stacked in big long stacks; then the top was rounded off to shed the rain.

While Louise raked, our older children looked after the younger ones at the tent. Grace used to bring lunch to us in the field and any that was left she gave to our kids. The two oldest ones made bannock and cooked it in a frying pan over the campfire; sometimes they took some of it up to the house for Grace. She really liked it and gave us eggs, milk, potatoes and other garden vegetables, which she never charged us for. Louise cooked our meals over a campfire.

Some years we would take a week off from work early in July and go to the pilgrimage at Lac St. Anne. Mr. Sharkey took a school bus load there each year. We tried to go to the Clearwater Lake Stampede and the. Lea Park Rodeo. We went to the annual F.U.A. picnic the farmers held on Section 7, which is across the road from the south edge of the Reserve.

After the family was old enough for school we could only camp at the job in July and August, because, after we got the family allowance, it was cut off if the kids missed too much school. Louise stayed home while I went out stooking and threshing.

Eliza's graduation at Elk Point, May 10 1971

We have ten children. George, our oldest, went through grade eleven and married Ina Quinney, daughter of Batiste and Elizabeth Quinney. Thomas Quinney is her grandfather, and Charlie and Harriet Quinney were her great grandparents. George drives a school bus and this year was elected as one of the Band Councillors. Francis married Mary Grace Stonechild of Onion Lake; they live on the Frog Lake Reserve. Irene went through grade twelve, married Rick Dillon of Onion Lake, and they live at Onion Lake. Eliza finished grade twelve and works at the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton. Richard took grade eleven and works on a seismograph crew at Fort McMurray. The others, Sandra, Raymond, Ronald, Dorothy, and James are at home going to Heinsburg School.

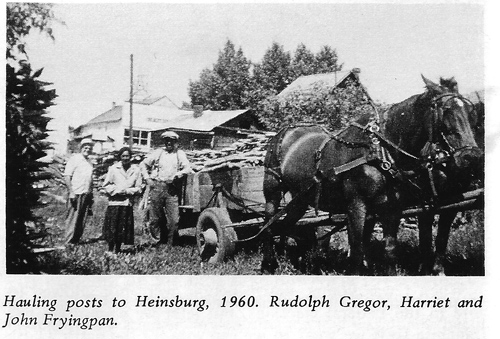

I don't work for the farmers much now. This summer Louise and I have been camping where we cut posts and treat them in a bluestone pit before we take them to be sold.