THE IMMIGRANT'S SAGA (995 - 1929)

by Tom Johre

For a family to leave the familiarity of its native land, and embark on a five-thousand-mile journey to foreign shores, must take a resoluteness of somewhat the same quality as that of Leif Erickson, who was the first European to see the towering cliffs of Labrador. His landfall, where he spent the winter, was Vinland, a portion of which is known today as L'Anse au Meadows, Newfoundland, which could very well be the birthplace of the first child of white parents to be born in North America, nearly a thousand years ago. His name was Snorri Thorfinsson, son of Gudrid and Thorfunn Karlsefni. No doubt, Leif found grave dangers in his epic journey, as we realize when we read in th sagas of encounters with the feared Skraelings in a hostile land. Yet, immigrants who arrived here in the late twenties and early thirties, as they did by the droves, also faced, possibly, the greatest hostility that modern man had ever been exposed to. The Great Depression, a world-wide catastrophe of near-to-unequalled proportions, and they were caught in its midst in a strange, if not formidable land.

On a bright April morning we waved good-bye to our ancestral home, and walked to the docks at Dalen, Norway, the first step of a long and trying journey. As the departing boat rounded the last bend, we saw the final glimpse of waving white hankies of our once good neighbors; then they were gone. There must have been choking tears, but they were not noticeable to a carefree eight-year-old boy. It all seemed so exciting! Landing in England, we went overland by rail to Southampton. There we boarded an ocean liner by the name of Ascania. It now became apparent that a different element was creeping into our life style; the liner was no Queen Mary, but an immigration ship, built for utility rather than comfort.

One of the most unusual experiences of the ocean voyage was an eight-year-old boy's adventure on a day when he was allowed to go to the washroom by himself. He became hopelessly lost and eventually ended up in the hold of the ship. Here was a huge cave-like area with rough plank floors and low ceiling, and in spite of the poor lighting, he could see through his anxious eyes literally hundreds of people sitting huddled on the floor in family-like clusters. Beside them were tattered suitcases and boxes which held all their meagre belongings and a cache of food, enough to carry them across the ocean. By their dress it was evident that these were Central Europeans and undoubtedly had been taken on at sea during the night, to be shipped to Canada as farmers or labourers. Likely hundreds of them worked out their passage as section men, which is still in evidence today (the hewers of wood and the drawers of water).

In May of 1929 we landed in Halifax and started our overland journey to western Canada. We travelled by C.P.R. and this is what can be remembered of the trip west. We rode through what seemed endless hundreds of miles of muskeg, half-dead scrubby spruce and out-croppings of rock. At this point of the journey I'm sure Mother and Dad would have turned back, as being ignorant of what lay ahead, they felt this must be what the land was like for the rest of the way. And to wrest a living from this wilderness would indeed be a hopeless task. Actually we were travelling across not too great a stretch of Northern Ontario. Our next stop-over was Winnipeg, where we were met by a Reverend Langley. Here Dad purchased a Remington 22 slide action rifle, which proved to be a real bread winner. You might say that it sort of "Won the West" by supplying an endless number of prairie chickens and partridges. We can remember many a crisp bright morning as we trudged through the snow to Norway Valley School, where flocks of prairie chickens would be sitting in the hoar-frosted tree tops, looking ever so much like big apples.

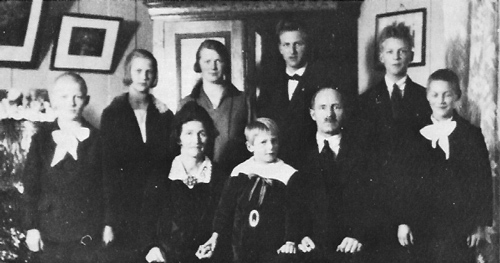

Halvor Kristi Margit Olous Gunnar Barney Tone Tom Gjermund

When we eventually arrived at Elk Point, Alberta we were met by Reverend Lorenson. The following day we took the mail truck, driven by a Mr. Johnson, and after what seemed like such a long time of rattling and shaking over ruts and rocks, we came to Ole Tweed's Post Office in Norway Valley. We were deeply grateful for having finally arrived in the promised land. Reverend Lorenson had also met other people at other times in Elk Point, among them being a Scandinavian, whose name I cannot recall. When this immigrant arrived, no Reverend Lorenson could be found in the crowd of people, until the Reverend Lorenson heard someone say, "Vor er denne forbanade presten?" Evidently Reverend Lorenson, understanding the strains and frustrations of an immigrant, took it in good stride, as he later, with much merriment, related the incident to Lauritz Enkenhus.

Our first meal in Norway Valley was at Anders Odegaardren's; our first stay at John Thorson's. How they lightened the burdens of the newcomers! Next we moved into the vacant house of Gerhard Gunderson. Here we discovered the full impact of the sign that read "Quarantine", on the cabin next to ours on the boat. It should have read, "Quarantine - Scarlet Fever", as we three boys came down with this dreaded disease. By the grace of God, we pulled through, but undoubtedly it left its mark, to re-emerge in later years.

Our first day at school was not a success. We got as close to the school as the nearest poplar bluff, and there we stayed until dinner time, ate our lunch, then started slowly homeward. The next day, however, was better. Our teacher was Mr. George Douglas and he rechristened me from Torbjorne to Tom. My other brothers' names were still recognizable. It was at this time that the schools had a program for paying the children to collect crows' and magpies' eggs, also gopher "scalps". If my memory is right, the money paid was one cent per gopher tail, one cent per egg, and five cents for a pair of crow or magpie feet. It was a wonderful scheme! It not only allowed boys and girls to make a few pennies, but also to enjoy the beauty of their surroundings, for the area was a playground of lakes, hills and trees.

It seems rather ironic that a communtiy such as this, even though at its lowest ebb in material gain, was possibly at its happiest, certainly its most populated. Some of the names that come in passing are John and Kari Thorson, Anders and Anne Qdegaarden, Knut and Befit Qdegaarden, Oscar and Vena Gunderson, Vraal and Dagne Kleven, Everett and Gunhild Helgerson, Olaf and Helen Tweed, Knut Vinge, Gundar Dalen, Jens Grenrud, Ted Thorson, Aslak Benson, Gus Brocke, Ed Lider, Dick Midgley, Millerkee, Bird, Atlas, Vic Anderson, Parenteau, and their respective families.

It was also in Norway Valley that the first business venture was undertaken. As we quickly caught on to the use of the language, an ad was spotted in one of the farm papers, "Make money selling Gold Medal Christmas Cards." The coupon was filled in and mailed, and before long a magic parcel arrived. They didn't sell very well; my net earnings being $1.83 for trudging many a weary mile through the ever-deepening snow. New hope was regained, however, the following spring, with Gold Medal Garden Seeds. They sold like hot cakes, Mother being the principal buyer.

Home on the range

In the fall of 1929 Vic Anderson took over the Gunderson place, and we in turn moved to the Sanders' homestead, where we spent the winter. W. missed Oscar Gunderson, as he was a fun-loving and 'jovial fellow â willing to take full advantage of a totally inexperienced and naive newcorner. He once took Knudsons and Mother for a ride on a hay rack, at a dead gallop across unworked breaking. Then there was the time Oscar and we three boys found a nest of rotten chicken eggs and set about having a fight with this deadly ammunition, not to mention the "strange" cow teat that he beckoned me over to see. On closer examination I got a stream of milk full in the face.

The winter of 1929-30 was not easy. Vraal Kleven had given Halvor a pony that was deemed too old for further work, and it would seem, was further deemed to no longer enjoy the open range. The result was the finest of meat balls; half horse and half pig, relished by one and all, including neighbors that occasionally dropped by. No doubt, should any of them read this epistle, it will be their first revelation of having eaten horse meat.

In the spring of 1930 a final move was made to land purchased on the south side of the Saskatchewan River, immediately across from the Norway Valley District. Jens Grenrud and John Thorson each took a wagon load, while two milk cows and their calves were driven behind. Our "Home on the Range" was humble indeed; an eight-byten log shack, partly built into a cut bank, with poles and sod for the roof. A tent provided we three boys with a place to sleep, and being close to a spring, we saw for the first time fire flies. We had not an inkling of what they were. Never had the imaginations of three boys been more active. For certain they were Indians on the war path, for not only did we see the flashing tomahawks, but also the war-painted faces and feathered head gear as well. Any moment now the blood-curdling yell of the braves would send them into our camp. Morning came, however, and with it the growing realization that it must not have been an Indian war party after all. It was almost a disappointment.

In the fall of 1930, Gjermund Johre died, having been in Canada for less than one and a half years. In March of 1932 I was admitted to the Junior Red Cross Hospital in Calgary, with T.B. of the knee, where I was to remain for two and a half years. We were now in the grips of the depression, and in Calgary a freight train going east would be covered with hobos. Hours later a train going west would be carrying a similar load, coming and going from heaven only knows where. It seemed as if a plague had swept the land. For many all hopes and dreams were shattered beyond belief. Some areas fared worse than others and cities were harder hit than the country, though parts of rural Saskatchewan were hit worst of all, as the depression, coupled with a severe drought, brought the people to their knees. The fact that these areas flourish today must be a lasting testament to the courage and will of these rural people.

But none were left unscathed. Prices of farm products were at an unheard of low: eggs, 4cents per dozen; butter, 8cents per pound; oats, 6¢ per bushel; barley, 9¢ per bushel; and Wheat 114 per bushel.

A mail order list from a 1933 Eaton sale catalogue looked like this:

Men's 3-piece dress suit ................................................... $10.95

9-ounce denim bib overall .79

Men's genuine horsehide gloves ............................................ .53

Woollen work socks ........................................... .18

Men's work boots ............................................................... $1.65

Carlsbad cowboy hat, 7 "crown ......................................... 1.49

Sheer voile dress .................................................................... 1.95

Ladies' woollen winter coat ................................................. 7.49

Ladies' hat ......................................................... .69

Ladies' woollen cardigan ..................................................... 1.69

Ladies' panties ............................................................ 4 pair/1.00

Ladies' patent leather dress shoes ...................................... 1.79

Kaschie lighter .......................................................................... .25

Premium stock pocket knife ................................................. .50

Pocket watch ......................................................................... 1.00

12-person dinner set ......................................................... 10.95

Regal scrub board ................................................................... .28

In our new location on the south side of the river, we were cut off from all traffic, as there was no road leading into the river valley other than winter trails made by outfits coming onto the flats for firewood and building logs, both being quite plentiful. In 1931 enough road work was done to allow a threshing machine through, with some difficulty. By the mid-thirties this had become a well-travelled winter road, leading up to Heinsburg and to the north side of the river. Hauling was an all-winter chore; grain to town, wood for the cook stove and heaters, huge ice blocks cut from the river for the ice house to keep the food and particularly the cream cool, but most important, feed from the south side of the river to the north side. Hundreds of loads were hauled during the winter months from straw stacks in the Riverton area.

One late afternoon Ole Enkenhus, standing by his cabin at the river, counted eighteen rigs. From this vantage point he could see up and down the river, as well as both sides of the river hills. Often he would see five or six outfits loading up ice, and rigs coming back from Heinsburg, including sleighs for hauling grain, cutters pulled by a light team of drivers, and of course the huge straw racks filled to overflowing with oat, barley or wheat straw. The Cooke boys, Doc, Dave and Doug, hauled all one winter to their cow herd wintering on the Nelson river flat. One day they would come past with two four-horse loads, and the next day with one four-horse load. This continued every day but Sunday, until the river was no longer safe to cross.

One bright wintry night, far past the usual time for the feed haulers to have gone by, the familiar sound of steel runners could be heard above the softer jingling of the trace chains. As ever so slowly it drew nearer, down along the winding road, a man's muffled voice could be heard, urging the weary team on. At last a lone figure,-huddled on the frozen bundles that barely covered the rack floor, came in sight. With nearly frozen feet and tired hands, he slowly edged his way off the rack, to almost drop to his knees, as his feet touched the ground. Walking for him was painful, as, staggering, he gasped the cold, biting air. Quickly we helped the nearly frozen old man into the house. As he slowly removed his outer clothing it seemed to send a chill into the room! On his feet he had ankle-high gum rubber boots, over a thin pair of cotton socks. His coat was made of heavy black leather that became almost brittle when exposed to the cold. A faded, thread-bare bandana hung around his neck. His inner mitts were a nest of haphazard bits and pieces of worn-out socks and underwear, no doubt of his own invention. The only clothing of any real warmth was an imitation fur cap with big shawl-like ear flaps and tie strings. Sitting in the flickering shadows of the coal oil lamp, watching this lonely old man, feelings of despair, mounting to anger, became apparent. And ever the question, "Why?"

After a warm meal, along with crusty home-made bread and butter, not to mention Mother's generous cups of coffee, he thanked her warmly but declined our offer to have him stay the night. Our thoughts were not only for the driver, but also the horses. They were noticeably weak, with bony hip joints and ribs showing through their shaggy winter coats; thus the small load of bundles that barely covered the rack floor. After helping him hook up his team, we stood and watched him disappear into the night, until at last the sounds of the winter traveller grew faint, to be no more.

These were the years of the thirties. The years of the Great Depression. Its scars on human souls have been deep and lasting. Little did we know that as we struggled against God and man, a crisis of even greater consequence was spawning - the Second World War, and its aftermath. Finally we reach our present day, which in many ways reminds one so much of Oliver Goldsmith's writings in "The Deserted Village", from which is taken this excerpt:

"Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay."